Straddling the Line Between Sick and Healthy

When I was first diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, I thought I’d be sick forever. I saw on the interwebs people with Crohn’s disease never getting better. Then the pendulum swung the other way: I felt very strongly that my Crohn’s disease would go into remission and I would not be plagued by illness for the rest of my life.

I envisioned remission basically looking like my before-Crohn’s life. I fantasized about being active and busy. I imagined a life without constant doctor’s appointments, medications, and naps. I believed I wouldn’t have to think about my health so much.

In many ways, remission is easier. I don’t restrict my diet (other than gluten). I rarely see doctors. I don’t need infusions anymore. I can do a workout and still function for the rest of the day.

But “healthy” still feels like a moving target. Some days I feel like I’ve hit the mark - there are no aches and pains, I am full of energy, and I feel relatively “normal.” Other days, I wake up feeling like I got hit by a truck merely because I went to a dinner party the night before.

I hate bars that smell like pee.

This “moving target” was very apparent last weekend. My best friend had her 40th birthday party at a bar. It felt important to attend her party, so I monitored my sleep and water intake and was careful not to overbook myself during the week before the party. I declined an invitation for the day after the party because I would need to recover. I prepared myself for the long, loud, social night. Knowing that an event like this would probably drain me, I made every attempt to preserve my energy and optimize my chances of enjoying myself.

I felt great on the day of the party. I drove up to Seattle and spent the day with a different friend. We went to the group dinner beforehand. By the time we’d arrived at the bar, I was tired, uncomfortable, and feeling much less tolerant. I got overstimulated by the loud music, the crowd, and the urine smell. I like to dance but didn’t have the energy. I wanted to socialize, but I had to yell to be heard. My feet hurt, my dress was poking at my shoulders, and I became increasingly agitated. I imagined how I’d feel tomorrow if I toughed it out. My head throbbed just thinking about it.

I slithered out of the bar 45 minutes after I’d arrived. I didn’t say goodbye to anyone because I was too embarrassed about my reasons for leaving. I missed the party.

During my drive home I ruminated on this experience. I felt disappointed and guilty. I struggled to understand why I couldn’t tolerate one party, just like everyone else. Why was everyone else laughing and enjoying themselves, and I wasn’t? I felt scared that I’d never move about my life with no restrictions.

This is not what I expected being in remission would look like. I don’t see myself as sick, but I’m clearly not healthy either. So what am I?

Am I sick? Am I healthy?

When I reflect back on everything my body has been through, I logically understand why I’m still adapting to an illness. The disease, and the medications I took to treat it, changed my body completely. I endured persistent and severe physical pain which has altered my mind forever, making me more cautious with my body and less likely to see “pushing through” as an option. In other words, I don’t have symptoms of the illness I was diagnosed with, AND I am still suffering from the effects of it.

Being in neither (or both?) the “sick” or “healthy” box is unnerving. How do I validate the state of my health (to myself or others) if I’m not firmly planted in one box or the other? I wanted a clear definition. So I went looking for one.

I didn’t find one.

But here’s what I did learn (and it’s even better).

What is health?

Our culture (and medical system) tend to think that illness is episodic. In this view, if you don’t have a disease, then you are well (healthy). This is the basis of the World Health Organization view, and probably represents the position of most people. This is not to say that there is no consideration given to a broad picture of health and illness. But like I noted above, I don’t know of another way to think of it, except in the broader context.

From this perspective, health is never static. In fact, it’s so transient and fleeting that you can’t define it outside of the context it’s in.

Let’s look at a case scenario using a fictitious man named Sean. Sean is a 42-year-old male with chronic pain related to a spinal injury when he was a college football player. Sean’s parents both died of cancer, most likely from chronic lead exposure. Sean has a high-stress job as a paramedic. When Sean was 6, he got a severe case of the Epstein-Barr virus. Throughout his lifetime he has broken a toe, had a severe sunburn or two, was bit by a dog, had a couple of minor car accidents, and recently noticed a strange rash on the back of his leg. He eats organic food but only started this about three years ago. There were times in his life when he had little body pain. There were periods when his immune system seemed fine but one winter a seemingly harmless head cold turned into pneumonia, and he was sick for three months straight. Sean constantly fluctuates between feeling ill and feeling well.

Sean’s health is influenced by a host of variables, including but not limited to past injuries and illnesses, exposure to toxins, stress, and the sun, trauma to the body, immune reactions, inflammation, and viruses. He has been exposed to several physical, biological, and sociocultural hazards. If you observe the 42 years Sean has been alive, his health was never constant. His body was adjusting to changes over and over again, leaving Sean to feel sicker and healthier at different times.

In that regard, optimal health is not a condition of an individual, but a state of interaction between humans and their environment. It is a ceaseless struggle between a basically hostile environment and a series of defenses we are equipped with and which we add to when necessary.

Health is a ceaseless struggle between a basically hostile environment and series of defenses we are equipped with and which we add to when necessary.

Our goal is to reach a state of balance. This may be accomplished by decreasing the threat of the environment (like reducing stress and exposure to toxins for example) or by raising the capability our body to defend itself (by eating nutritiously and exercising, for example).

“Sick” and “healthy” don’t cancel each other out. You’re never one or the other. You’re always some version of sick and some version of healthy.

Health is on a spectrum

If your health feels like a moving target, well, that’s because it is!

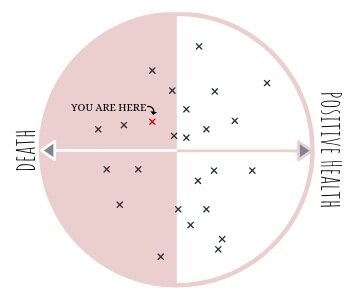

Health and disease exist along a continuum, and there is no cut-off point. The lowest point would be death, and the highest would be optimal health. Your health fluctuates within a range of optimal well-being and dysfunction. It is a process of continuous change, subject to numerous subtle variations.

Your health is a constantly moving target along a continuum with no cut off point.

As much as we’d like it to be, health is not a state to be obtained once and for all. There are levels of health, and there are degrees of illness. As long as we are alive, there is some degree of health in us.

Neither illness nor wellness defines you

So I didn’t dance the night away at my friend’s 40th birthday party. So what?! Despite my best efforts, hazards swooped in and had different plans for my evening.

No matter how much control you think you can assert over your health, there are always variables outside of your control. You can choose to wrestle with disappointment when your health doesn’t give you what you want, or you can choose not to let those emotions consume you or define you. It’s not helpful to criticize yourself and obsessively look for answers to questions there are no answers for. If the state of your health is always changing anyway, it’s unworkable to control it or reduce it down to some arbitrary definition.

Loosening your grip on “optimal health” is freeing. If you want to go for a walk but fatigue tells you to sit your ass down, you can make a choice based on what the situation affords, not on your fear of not being healthy. If you don’t hold yourself to an unattainable standard, you can move and adapt more flexibly to the context.